Although a basic part of human nature and “one of the perspectives that gives us the most insight” into that nature, communication processes remain complex. As a result, no fewer than four alternative views of communication have arisen that shed light on the complexity inherent to human communication. These include: the transmission, behavioral, interactive, and transaction emphasis.

Transmissional perspective – In this perspective, communication is viewed primarily as a digital linear process (Shannon and Weaver, 1949) or communication system modeled after principles of general systems theory (Richey, Klein, & Tracey, 2011). In this process, communication begins with a source (i.e. a person) selecting a message, converting the message into a signal (encoding) and sending the encoded message/signal over a selected communication channel. In the process, the message may be interrupted by any number of noise sources which can distort or alter the message before it is finally received (decoded) by the intended destination (i.e. a receiving person). Once received the message is interpreted for meaning and the receiver changes roles becoming the new sender.

communication system modeled after principles of general systems theory (Richey, Klein, & Tracey, 2011). In this process, communication begins with a source (i.e. a person) selecting a message, converting the message into a signal (encoding) and sending the encoded message/signal over a selected communication channel. In the process, the message may be interrupted by any number of noise sources which can distort or alter the message before it is finally received (decoded) by the intended destination (i.e. a receiving person). Once received the message is interpreted for meaning and the receiver changes roles becoming the new sender.

Behavioral perspective – In this perspective, communication is described as a stimulus-response situation in which the sender stimulates a meaning response in the mind of the receiver (Heath & Bryant, 2000). In form, it is quite similar to the Shannon-Weaver transmission model in terms of its linearity, general process elements and order of sub-processes. However, the key difference is that the message is the central element of the process and is itself the stimulus – and not the sender. Another difference is that the behavioral perspective values feedback from the receiver as essential to clarify an intended message. The behavioral model most linked to education is the Sender-Message-Channel-Receiver Model (S-M-C-R) (Berlo, 1960).

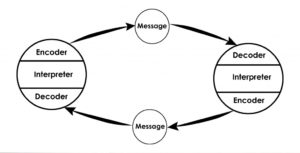

Interactive perspective – Although the message still has the dominant role in communication, the key emphasis here is on the social interaction process that occurs through the messages. This perspective views communication as less linear and mechanical in that the senders and receivers are operating simultaneously to send and receive messages. Schramm’s Model (Schramm, 1954) is one of the first to illustrate this social aspect. Communication is constant and dynamic, yet like the behaviorist perspective, depends on a process of continual feedback. Also, since communication is dynamic and constant, there are actually multiple channels of communication being used simultaneously. Finally, once decoded, the message are interpreted and thus “understood by individuals based upon their own backgrounds and understandings of the particular situation” (Richey et al., 2011).

Transactional perspective – Determining meaning is seen as “a matter of sharing and co-creating meaning among actively engaged participants” (Richey et al., 2011) and not merely as an interpreting process as other perspectives understand it. Like the interactive perspective, the situation, backgrounds, and previous experiences of all participants all determine the flow of communication. Representative of this perspective is Campos’ (2007) Ecologies of Meaning Model of Communication, which blends Piaget’s “communication as a process of exchanging values” (Richey et al., 2011), Grize’s theory of communication as a process of schematization in which “interlocutors help to interpret each other’s and one’s own world”, and Habermas’s model of social cooperation which emphasizes a connection between the individual and his social system (Campos, 2007). Though similar to the interactive perspective, this perspective summarizes communication as “a matter of constructing individual and contextualized knowledge in cooperation with others” (Richey et al., 2011) and not simply as messages being transferred and interpreted between one individual and another.